Rush Family History

The Story of the Rush Family

Links:

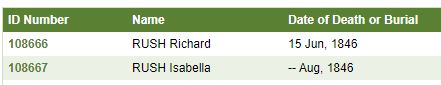

Wellington City Council Cemetery Records, Bolton Street. Search for:

- Richard Rush

- Isabella Rush

View the History of Bolten Street Cemetery.

Download and print the full story of Richard Rush prepared by Dale Hartle in August 2001 (17 page pdf).

View an article written in the Wellington Spectator about Richard Rush and his dog.

View Society of Australian Genealogists - Ticket of Leave - Richard Rush. Requires purchase.

View New South Wales State Records Authority - Convict Archives - Certificate of Freedom: Search for Richard Rush, Year 1832, Ship Planter.

Richard Rush, 1799-1846

This page documents the life of Richard Rush, the second husband of Cecilia Eliza Herbert.

Richard's English Family

Richard Rush was born on 20 February 1799 in Orsett, England. He had been married prior to coming to New Zealand but emigrated alone as a widower. His first wife, according to his son John George Rush's second marriage certificate, was Maria Steel who died aged 26 years on 22 April 1827, shortly after their son John George was born. Apparently there were four older children born in England (Sarah Steel Rush, born 14 May 1819, Richard Rush, born 29 November 1820, William Rush, born 7 April 1822, and Maria Rush, born 26 October 1823, all in Dunton). No birth records for John George Rush have yet been discovered. Work continues on researching these other children.

Richard's Conviction for pig stealing

Richard emigrated to New Zealand from Sydney, Australia, in December 1840. Richard Rush was in fact a convict who was tried and sentenced at the January 1832 Quarter Sessions in Chelmsford (just north of Aveley) for Larceny, the offence being "pig stealing". Richard's occupation on his Convict Transcript states "ploughs, reaps, milks, sows", which means he was probably an agricultural labourer living on a landowner's property, and working on the farm.

The transcript of Richard's conviction shows the penalty he was given: "Richard Rush being now convicted of Larceny and ordered and adjudged by this court pursuant to the Statute in that was made and provided to be transported beyond the seas for one term of seven years to such place as His Majesty with the advice of his Privy Council shall think fit to declare and appoint."

Once convicted, people were held in local prisons or prison hulks until space was found on the transportation ships leaving for New South Wales, and Richard was finally placed on the ship "Planter" which left Portsmouth on 16 June 1832. On board were 200 male and 200 female convicts.

Convict labourer

The record of a convict's arrival in the Colony is called a convict indent. On arrival, the first major event in a convict's career was assignment, with males often being assigned as labourers to private settlers. After several years of satisfactory service, convicts were entitled to apply for a "Ticket of Leave" (a form of parole) and with continued good behaviour they would eventually obtain a "Certificate of Freedom" or Pardon.

Richard served seven years as a farm labourer helping to break in the land near Singleton in the Hunter Valley north of Sydney for settler Andrew Loder, and was set free in October 1839. His indent records described him as being around 5' 2" tall, with brown hair and blue eyes, and a dimple in his chin.

Having been released from his conviction, Richard was free to leave, and we believe he came to New Zealand probably as a crew member aboard a migrant or trading ship from Sydney. He obviously could not return to England, and the fate of his other children, except for John George, is unknown. We also wonder if the children he left behind ever knew what happened to their father, and whether he was in contact with them after he left England.

Richard marries Cecilia

The newly widowed Cecilia Rodgers must have met Richard Rush soon after his arrival in Wellington, and they were married sometime in 1841, since their first daughter Sarah Ann Maria was born on 13 January 1842. Three more daughters were born to Richard and Cecilia between 1843 and 1846 - Cecilia, Isabella and Anne. Isabella, the third daughter, born on 1st August 1845, died shortly after Richard at the age of one from "teething complications".

Richard's son John George was 15 when he arrived in Wellington some time in 1842 aboard the "Esther", a schooner which plied the eastern Australian coast from Botany Bay to Tasmania and New Zealand for several years. John George, who went to sea with his uncle as a lad, must have been in Australia looking for his father and may have discovered that he had gained his freedom and gone to Wellington. He obviously found his father and decided to live with the family in Taita.

Richard is reported as being a witness in the inquest into the death of Mr Archibald Milne, in the local newspaper in December 1841. He was a barman at the time. His evidence was:

Richard Rush sworn: "I live at Mr Allen's; I recollect Mr Milne coming there on Tuesday, about 2 or 3 o'clock, but am not quite sure about the time. He called for three glasses of porter, which I served him with; he drank one glass himself, and treated two other persons with the others; he stayed about half an hour; was quite sober."

Source: New Zealand Spectator and Cook's Strait Guardian, Volume II, Issue 100, 22 December 1841, Page 3.

Richard murdered

Tragically, Richard was murdered in Lower Hutt on 15 June 1846, amidst much native unrest at the time. He had gone out at about 8 o'clock on the morning of Monday 15th June, to look after a horse which had strayed away during Sunday. He went in the direction of Barton's paddock, where he was surprised and tomahawked by Maoris. They inflicted three deep wounds in his skull. His dog was standing by his body faithfully guarding the remains of its master, and it was found impossible to remove them without first destroying the dog. His murder was reported extensively in local newspapers at the time.

The "New Zealand Spectator, and Cook's Strait Guardian" of Wednesday, June 17, 1846, reported what happened:

Another barbarous murder has been committed on the Hutt. Another victim has fallen to the insatiable thirst of blood which distinguishes the adherents of Rangihaeata. The deceased, Richard Rush, was an honest industrious settler who lived on the right bank of the river, and was known as the Carrier between Wellington and the Hutt district. On Monday morning he went as usual to catch his horse for the purpose of following his occupation, when he was savagely tomahawked by a party of the rebels, who had returned again to their old position opposite the camp. The murder was committed within a few hundred yards of Mr. Barton's house, there was no attempt at concealment, on the contrary the perpetrators of the horrid deed exultingly told the friendly natives from the other side the river, "that they had killed another of their pakehas, an old man, and that they had better take away the body," and afterwards commenced firing on the camp. A party of the militia repaired to the spot, and found the body of the unfortunate man, whose death had been caused by three deep wounds on the skull inflicted by a tomahawk; his dog was standing by the body faithfully guarding thd mangled remains of his master, and it was found impossible to remove them without first destroying the dog. The deceased has left a grown up son by a first marriage, and a widow with four young children. Including the Gillespies, eleven persons have been slain by the rebels. Eight were killed or died from wounds received in the attack on the camp, three have been murdered in cold blood under the most revolting circumstances. And yet the authorities do nothing! Now the settlers wish to know of those with whom the responsibility rests, how they can in any way justify their present inaction, when they see such lamentable consequences resulting from it. Is a handful of natives to be permitted to burn and destroy the property of the settlers, to riot in murders of the most cruel nature? Are crimes of the deepest die to become matters of daily occurrence, while they sit still and do nothing? They have already succeeded in impressing the rebels with a thorough contempt of British authority, as is evidenced by the excesses and crimes of which they are guilty. This is not a war, for the rebels have no aim or object beyond the gratification of their thirst for blood. A band of savages, the very refuse of the natives are let loose on the District to rob and murder without let or hindrance, and with an overwhelming force at their command the authorities look on indifferent and inactive, provoking these miscreants by their supineness to further outrages, while the settlement is shaken to its foundation, and the settlers and natives look on with mingled horror and astonishment. How long, we repeat, is this state of things to last?

The following report was brought from the Hutt this morning at the moment of our going to Press. Last night about midnight, the friendly natives reported to the officer in command at the camp, that the rebels had crossed the river and were blockading the road between the camp and the stockade. The militia and soldiers were ordered out this morning at daybreak to attack them, and it is reported that they were both driven back to the camp by the rebels, with one officer and four rank and file wounded. At the time the despatch left, a general attack on the camp by the rebels was hourly expected.

Source: New Zealand Spectator and Cook's Strait Guardian, Volume II, Issue 92, 17 June 1846, Page 2

NATIVE WAR AT WELLINGTON, Another awful Murder in the Hutt. It was generally reported in town during the past week that the rebels had again lei't the Hutt for Pauhautanui. On Sunday it was stated that Ranghiaiata, with most of his followers, had started from his pa for Rangiriki, in order to effect a junction with the Taupo tribe, and to destroy a fortification which was being erected by the Ngati-awas, in order to stop the passage of the Taupo tribe along the coast. The hostile natives having threatened to burn tie premises of Messrs. Stilling and Barton, for the last three weeks a picket of militia and mounted police has been stationed in the last-named gentleman's house, whilst a line of sentinels kept up communication from thence to the bridge. The picket is called off at eight o'clock in the morning. These reports were no doubt circulated ly the rebels for a purpose; and many of the Hutt settlers began to return to their land for the purpose of chipping in wheat, feeling secure, from the report, that the rebels had evacuated the valley. On Saturday night a few ducks were carried off from Mr. Barton's land, inducing a suspicion with some, that the natives were still lurking about. It is now our painful duty to record the fact of the presence of the rebels on the Hutt, from the painful circumstance of the murder of Mr. Richard Rush, a Hutt settler. On Monday evening the inhabitants of Wellington were again thrown into a state of great excitement, intelligence having arrived from the Hutt to the effect that a man had been found murdered in the valley that morning. The unfortunate deceased, Richard Rush, had gone out about eight o'clock ia the morning to look after his horse, which had strayed away during Sunday. The murdered man went in the direction of Barton's paddock, and it appears that some of the rebels, who were lurking about in that quarter, surprised and tomohawked him, splitting his head into four pieces. After perpetrating the murder, the rebels hailed the friendly natives from across the river, informing them that they had killed a white man, mentioning the spot, and stating that they might have the body. Captain Hardy, the officer in command at the camp, at Boulcott's, sent out a body of military and armed police, who found the mangled remains of Rush, but fell in with none of the enemy. The Hutt militia, exasperated at being driven from their homes and at the murder of Rush and the previous murders of the Gillespies, threatened to cross the river and meet the rebels on Tuesday morning. Yesterday they made several attempts, at various points, to cross the Hutt, in order to put their threats into execution, but, owing to the late heavy rains, the river was not fordable. The murdered man has left a widow and four children to lament his loss; the widow is near her confinement with a fifth.

Source: Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle, Volume V, Issue 227, 11 July 1846, Page 74

The enemy admitted to have lost five killed and two wounded, among the number one chief named "Te Oro," and "Tapuke," the murderer of Richard Rush at the Hutt.

Source: New Zealand Spectator and Cook's Strait Guardian, Volume II, Issue 110, 19 August 1846, Page 3

[https://www.nzpictures.co.nz/HuttValleyTimeline-VoicesOfThePeople.pdf] page 229: 15 Jun 1846: Mon, Richard Rush, an honest industrious settler who lived on the right bank of the river and was known as the Carrier between Wellington and the Hutt district, was tomahawked by a party of rebels when he went as usual to catch his horse. This occurred within a few hundred yards of Mr Barton’s house. The deceased has left a grown-up son by a first marriage, and a widow with four young children. [1492] Richard Rush was killed at the Hutt Bridge. [1493]

References:

1492 New Zealand Spectator and Cook's Strait Guardian 17 Jun 1846

1493 Wairarapa Daily Times 11 Sep 1886 Reminiscences of the early Wairarapa Settlers by H. H. Jackson

The funeral of Richard Rush took place, and the body was interred in the Public Cemetery and was followed to its last resting place by a considerable number of settlers. The Rev R. Cole performed the burial service. It is intended to raise a subscription for his widow and children. [1507]

Reference: 1507 New Zealand Spectator and Cook's Strait Guardian 20 Jun 1846

Funeral

The funeral of the late Richard Rush, whose barbarous murder by the rebels was recorded in our last number, took place on Thursday afternoon. The body was interred in the Public Cemetery, and was followed to its last resting place by a considerable number of settlers. The Rev. R. Cole performed the burial service. It is intended to raise a subscription for his widow and children, and we earnestly solicit the attention of our fellow settlers to the appeal made to them in this day's Spectator on their behalf.

Source: New Zealand Spectator and Cook's Strait Guardian, Volume II, Issue 93, 20 June 1846, Page 2

For a second time, Cecilia found herself a widow, with few prospects and little means of support, struggling to raise her young family of five. See the story of Isabella.

Burial

Richard Rush was buried in the Bolton Street Cemetery in Wellington. In the 1970s the cemetery was reconfigured when the Wellington Urban Motorway was being reconstructed, and many graves were moved. There are also many unmarked graves in the cemetery, and no clear identifying plot for Richard has ever been found, so we do not know exactly where he was buried, but suspect it is near the footpath in Bolton Street, as many other burials in this area are of similar dates. No headstone can be found.

Probable Burial location - Richard Rush - Bolton Street Wellington.

You can view the Friends of Bolton Street website and view the following burial records:

Contact details

If you have any information or photos to add to this page, or any corrections, please contact Dale Hartle in Levin, New Zealand, by phone +64 021 45 34 24.